OPENING OF THE SYMPOSIUM AND WELCOMING ADDRESS

Wim VAN DER EIJK - Vice-President DG 3

Lady Chief Justice, Mr Justice Murphy, [Minister], Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to address you at the 16th judges' symposium here in Dublin. It is the first time that I speak to you as Vice-President of the EPO responsible for appeals and chairman of the Enlarged Board of Appeal. I am honoured to be part of the boards of appeal, which are an established authority in the international patent community. And I am of course honoured to address you, the distinguished guests at this event. I am convinced that we as we are gathered here in this symposium have an important role to play in the well functioning of the patent system in Europe. As the economies in Europe become more and more integrated, it becomes more and more important that the judicial instances in Europe develop a harmonised approach to patent law issues. The intense discussions on the creation of a unitary patent and a unified patent court are testimony to the fact that also the political authorities take this challenge serious. I believe therefore that it is more important than ever that all those adjudicating on patents in Europe share and exchange their ideas on pivotal issues of patent law. In that sense I look forward to the presentations and discussions we will have in the coming days. I hope that by the end of this symposium we will have a better understanding of the issues under discussion and the various approaches to them. Above all I hope we engage in the discussions with an open mind and are also ready to reflect on new ways to deal with certain issues in the interest of a truly European patent system.

The symposium is here so that we can share ideas, but it is also a good forum to learn more about the issues and problems facing each of us. I would like to start by sharing with you some of the recent developments within the boards of appeal and some of the issues facing us. In the second part of my speech, I would like to address the issue of our interaction with national judges and the public as well as the position of the boards of appeal in the framework of the unitary patent and the unified patent court.

My first topic is cautiously entitled "volume of work".

Volume of work

For years, the number of appeals filed with the boards of appeal has been increasing continuously. The development of new and settled cases before the technical boards of appeal in the past 5 years shows a clear picture:

Year | New cases | Settled cases | Difference between new and settled cases |

2007 | 2090 | 1661 | 429 |

2008 | 2409 | 1782 | 627 |

2009 | 2484 | 1918 | 566 |

2010 | 2545 | 1964 | 581 |

2011 | 2657 | 1875 | 782 |

As you can see, despite an increase in settled cases we observe a continuing trend that more appeals are coming in than we can settle. Therefore, the stock of pending appeals continues to grow, as do pendency times.

There may be numerous reasons for the increase in the number of appeals filed. An important one is that the number of applications for European patents has increased and is still increasing. The number of decisions by examining and opposition divisions is also increasing. With a relatively stable appeal ratio it is not surprising that also the number of appeals is increasing. Furthermore, we are observing that in specific technical areas the examining divisions are refusing many patent applications and this leads naturally to a greater number of appeals. One such area is that of computer-implemented inventions and so-called business methods. The boards dealing with this technical area are faced with a flood of appeals and have the biggest increase in pending cases. I note in passing that this trend reflects a state of disharmony in the global patent system. Many of these applications come from abroad, in particular the USA, where the approach to such patents is more liberal.

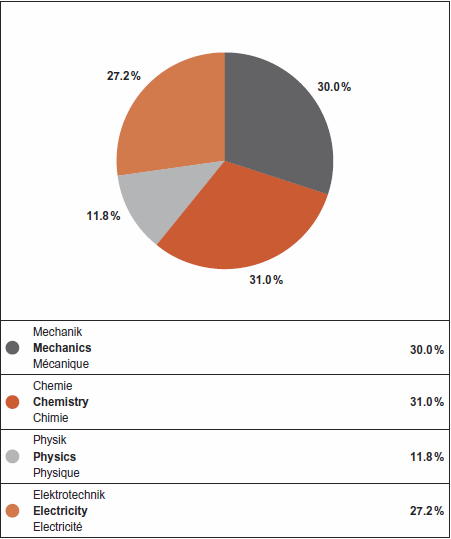

Below is an illustration of the incoming and settled cases per technical field in 2011 and of the appeals pending as at 31.12.2011.

New cases | Settled cases | Appeals pending |

| | |

One of the main priorities for the boards of appeal and for me as Vice- President is to address this workload issue. There is not one specific measure which can resolve this problem. And it cannot be resolved without the involvement of everyone in the Directorate-General "Appeals". Based on input received from the members of the boards of appeal and their support departments, measures are being considered which should have a beneficial effect on procedural efficiency and case management. The aim is to improve the efficiency of the procedures in order to increase the number of cases that are being settled without, however, touching on quality.

In order to bridge the gap between incoming and settled appeals efforts are also being made to focus on recruitment, succession planning and improved support for the boards of appeal. DG 3 is seeking to improve forecasting methods that would help detect evolving trends in the various technical fields. Given the different increases in the number of appeals filed in the different technical fields, this would mean that when new boards are set up in 2013 and 2014, the necessary technical expertise can be identified. With the variety of measures which we currently have in mind, I am confident that steady progress can be made towards stabilising and even reducing the stocks and pendency times of appeals.

Some of the measures just described will not have an immediate effect on the pendency times of appeals. It is thus important to be aware of the possibility of accelerated processing before the boards of appeal. The possibility to ask a board to deal with the appeal rapidly not only exists for parties with a legitimate interest, but also for courts. If you deal with an infringement proceeding in relation to a patent which is the subject of opposition appeal proceedings you may wish to contact the relevant board to request that the appeal is dealt with rapidly. You can rest assured that we take these requests very seriously.

Outcome of appeals

Another aspect of our work I would like to share with you is an analysis of the outcome of appeal proceedings. I would like to distinguish here between two types of cases. One is where the decision of the examining division refusing a patent application is appealed - these are the ex-parte cases. The other is where the appeal lies from a decision of the opposition division - these are inter-partes cases. As a point of information: of the technical appeals in 2011, 49% were ex parte cases, and 51% inter partes.

The figures are those for the year 2011.

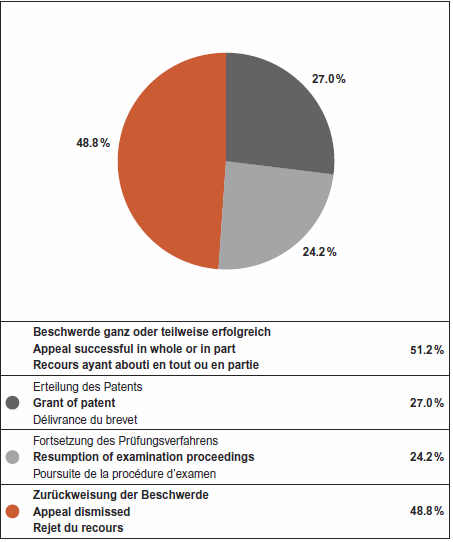

59% of ex parte cases were settled after substantive legal review, i.e. not terminated through rejection as inadmissible, withdrawal of the appeal or application, or the like. The outcomes of these are illustrated below:

In 51% of cases the appeal was successful in full or in part. In just over half of those cases the board ordered the grant of the patent. In just less than half of them, resumption of the examination proceedings was ordered.

Of inter partes cases, 69% were settled after substantive legal review. The outcomes were as follows:

In the vast majority of cases, there was no resumption of the opposition proceedings, but the board decided to order maintenance of the patent as granted or in amended form or revocation of the patent.

The interpretation of these figures has to be done with care. Many cases where appeals are successful are the result of amended claims or evidence and do not mean that the examining or opposition division got it wrong. Yet the often very different results for the party or the parties at the end of the appeal proceedings clearly confirm that the boards of appeal have a very important role to play.

There is of course also the important role that the boards play with their jurisprudence. My colleagues will highlight some pertinent topics in this regard in the course of this symposium. I would simply like to refer to two areas where interesting developments can be observed. Before I do this, let me say a few words about harmonisation among the boards.

Harmonisation among the boards

One challenge for the boards of appeal is to create a greater degree of harmony among the 27 technical boards on procedural matters. With the EPC being relatively brief on procedural matters, much is left to the discretion of the boards. The wish to have a more consistent practice on procedural questions has been mentioned by the outside world but is also expressed by many colleagues in DG 3. No-one can of course tell judges what to decide. But a process of informal exchanges of ideas and views on legal issues not related to an actual open case may eventually lead to greater harmonisation. One area where a tendency towards more harmonisation can already be observed is how the boards approach late-filed facts, evidence and requests.

Developments in the case law

Late-filed facts, evidence and requests

From time to time it can be observed that some parties to proceedings before the EPO do not put forward all the facts, evidence or requests before the examining and opposition divisions. Instead, they wait until the case has gone to the boards of appeal before presenting these. This has become a dangerous tactic. Article 12(4) of the Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal makes it clear that a board does not have to admit into the appeal proceedings facts, evidence or requests which could have been presented in the first-instance proceedings. One can observe a recent tendency in the case law to apply this article more stringently. Those who do not take the proceedings before the examining and opposition divisions seriously take the risk that facts, evidence or requests introduced only at the appeals stage are held inadmissible if they could have been presented before the department of first instance.

Whilst it may be a coincidence that this recent tendency in the case law has developed at a time when we are also considering the issue of procedural efficiency, it is nevertheless helpful in this context when proceedings are approached somewhat more stringently than had been the case years ago.

Petitions for review

Let me also say a few words about the case law that the Enlarged Board of Appeal has developed in its decisions on petitions for review.

You may recall that in 2007, in the context of EPC2000, this new procedure was introduced allowing parties who believe that there had been a fundamental procedural defect in the appeal procedure to file a petition for review with the Enlarged Board. Since the introduction of this procedure the Enlarged Board has rendered almost 60 decisions on petitions for review. Three petitions have been successful and the decisions of the boards of appeal were set aside and the appeal proceedings re-opened.

Almost 60 decisions is a considerable body of case law. Given that pretty much all of the cases concern an alleged fundamental violation of the right to be heard, some principles have by now been established and I would like to mention one in particular. One recurring theme in this respect is the argument that the board ought to have informed a party in advance about the decision to be taken and the reasoning for it, in order to enable it to present additional arguments and evidence.

The case law of the Enlarged Board of Appeal has established that there is no right obliging a board to inform the parties in detail before taking its decision about all the foreseeable grounds set out in the reasons for its decision. It is generally sufficient for the respect of the right to be heard if the grounds given in the written decision correspond to an argument put forward by any of the parties to the proceedings or by the board. The petitioner will have been aware of the argument and could have presented its views on it.

Having given you a short glimpse of case law developments on procedural matters (the substantive issues will be discussed later during this symposium) I will now turn to the boards of appeal and the public.

Informing the public

One important task of DG 3 is to inform the public about the case law of the boards of appeal. At the beginning of this year, the annual Official Journal supplement "Information from the Boards of Appeal" was published. It contains information about the business distribution of the boards of appeal as well as important texts concerning the appeals procedure such as the Rules of Procedure of the Boards of Appeal. The annual edition of the Special Edition "Case Law of the Boards of Appeal" appeared in July this year. It provides a systematic overview of the more important cases rendered by the boards of appeal last year. Work on the next edition of the Case law book, also known as the "white book", and published every three to four years has already started.

I would also like to mention that the searchability of decisions of the boards of appeal has been improved significantly in the last few years. A large number of search options is available, giving the user for example the option of identifying all recent cases rendered important enough by the boards to be circulated among all members of the boards of appeal.

DG 3 also has a role to play in supporting you and the general public by publishing information concerning national case law in the area of patent law. One publication which is of particular relevance to you is the comprehensive collection of national decisions entitled "Case law from the Contracting States". It was published at the end of last year and covers the years 2004-2011. A number of you have contributed to this publication by sending us decisions of particular importance from your jurisdictions and I would like to thank you for this support. We would like to provide this publication more regularly and rely on your support to make it as comprehensive as possible. We will therefore contact the relevant courts in order to establish the best way of accessing the national case law in your respective countries.

Interaction with stakeholders

One area to which I attach particular importance is the interaction with the stakeholders of the European patent system. We ought to understand their concerns and consider their feedback but also discuss developments within the boards and the role parties and their representatives could play to enhance the quality and efficiency of the appeal proceedings. I intend to hold regular meetings with stakeholders for that purpose.

Cooperation and exchanges with national judges

Of equal importance are our cooperation and exchanges with national judges. These take place in a variety of ways. The most formal one is the participation of national judges as external members of the Enlarged Board of Appeal. When the Enlarged Board of Appeal decides on a point of law referred to it, it is composed of 7 members - 5 legally qualified and 2 technically qualified ones. One or two of the legally qualified members can be replaced by one or two legally qualified external members if the case extends beyond the internal administration of the EPO. These external members are predominantly national judges and I am sure some of you are among them.

My predecessor as chairman of the Enlarged Board of Appeal made considerable use of this option. In seven of the eight decisions taken by the Enlarged Board in 2010 and 2011 on referrals, one or two legally qualified external members were members of the Enlarged Board. It is a practice which supports harmonisation and which has worked well in the past. For these reasons, I intend to continue with the practice of designating legally qualified external members to the Enlarged Board in all cases where the issues at hand go beyond the internal administration of the EPO.

This year the EPO has started a programme of internships for judges at the boards of appeal. The programme is open to national judges of Contracting States. Whilst not strictly speaking necessary, it is nevertheless useful if the national judges who wish to participate in the programme work in courts competent to deal with patent cases. The judicial internship programme lasts one month. Up to seven judges attend a one-week intensive training course on patentability requirements and the procedures of the boards of appeal followed by three weeks of shadowing a technical board of appeal. The first judicial internship programme took place in June this year. Both the national judges concerned and the EPO colleagues involved were of the view that it was a worthwhile exercise and should be repeated in future.

The Unified Patent Court and the boards of appeal

Let me now turn briefly to my last point which is of particular relevance at present. It is the plan for a unified patent court and the role of the boards of appeal.

I will restrict myself to making some observations from the perspective of the boards of appeal. First of all, it is to be noted that the projects are based on the concept that the proceedings conducted by the EPO, up to and including the appeal stage, will remain unchanged. For the Unified Patent Court, this means that this court will only take over the role of the national courts in the member states and has no role in the process of grant or refusal of a patent application.

This means that where an examining division has refused a patent application, the boards of appeal remain the only competent court to which an appeal against this decision can be directed. The Unified Patent Court has no competence in such cases. Where the boards of appeal confirm refusal by the examining division, the Unified Patent Court has no competence either.

The boards of appeal also remain competent to decide on appeals from decisions of the opposition divisions. Any decision revoking a patent cannot be challenged before the Unified Patent Court.

When it comes to decisions of the boards of appeal to maintain a patent or order the grant of a patent, third parties have always had the opportunity to have the issue of validity on the national level decided in the context of infringement proceedings by a national court. The Unified Patent Court now offers the possibility of a centralised attack on the validity of a European patent or a European patent with unitary effect. Given that the possibility of third parties to file oppositions against European patents before the EPO remains, the draft agreement foresees that the Unified Patent Court may stay its proceedings when a rapid decision is expected from the EPO in opposition (or revocation or limitation) proceedings.

The competence for actions against decisions of the EPO concerning the tasks that it is entrusted with in implementing enhanced cooperation lies with the Unified Patent Court. These tasks of the EPO are the administration of requests for unitary patent protection, receiving and registering statements on licensing, publication of the translations, collection and administration of renewal fees, and the administration of a compensation scheme for translation costs. The boards of appeal play no role with regard to these decisions.

So formally, things will remain unchanged for the boards. The creation of a unified patent court will however dramatically change the landscape. Today the boards are the only European judicial instance in the field of patents. With the creation of the Unified Patent Court there will be a second European instance, albeit with competence for a restricted group of EPO member states. As we are concerned about harmonisation of our approaches today, we must also in this new setting strive towards common approaches wherever possible. In that sense we will follow the developments closely and try to find ways to promote a common approach to legal questions. This cannot be done in a formal way, as the two bodies are independent and have to act on the basis of different legal provisions. But as we have found today informal ways of interacting and exchange, I am sure we will be also able to find ways in the future. Furthermore I am also convinced that the members of the boards of appeal, both the technical and the legal members, have valuable knowledge and experience. To the extent that it is legally possible, participation of board of appeal members in the work of the Unified Patent Court would be beneficial to the success of the new construction.

Conclusion

These reflections bring me back to the beginning of my presentation: the usefulness - I would even go one step further: the need - of cooperation and interaction between all those responsible for the administration of justice in the field of patents in Europe.

I thank you for your participation in this symposium and look forward to fruitful discussions and inspiring outcomes.