INFORMATION FROM THE CONTRACTING / EXTENSION STATES

DE Germany

Judgment of the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) of 2 March 1999

(X ZR 85/96) *

Headword: " Spannschraube" (Clamping screw)

Article 69 EPC and the Protocol on its Interpretation

Keyword: "Interpretation and extent of protection of a (European) patent - interpretation according to the overall content of the patent specification - understanding of a person skilled in the art - patent specification as its own glossary - equivalent embodiment (denied) - EP 0 319 521 - rules of interpretation"

Headnote:

1. Interpreting a European patent does not entail adhering strictly to the wording, but rather considering the overall context conveyed to a person skilled in the art by the content of the patent specification. It is not the linguistic or logical definition of the terms used in the patent specification which is decisive, but rather how they would be understood by an impartial person skilled in the art.

2. As regards the terms used in them, patent specifications constitute their own kind of glossary. If those terms deviate from the general (technical) use of language, it is ultimately only the connotation derived from the patent specification which is decisive.

3. The extent of protection conferred by a European patent cannot be extended to embodiments using alternative means which, either completely or to an extent which is no longer of practical significance, dispense with the success sought by the patent.

Summary of facts and submissions

The plaintiff is the exclusive licensee of European patent 0 319 521 (patent in dispute) (...).

Claim 1 of the (...) patent in dispute reads as follows:

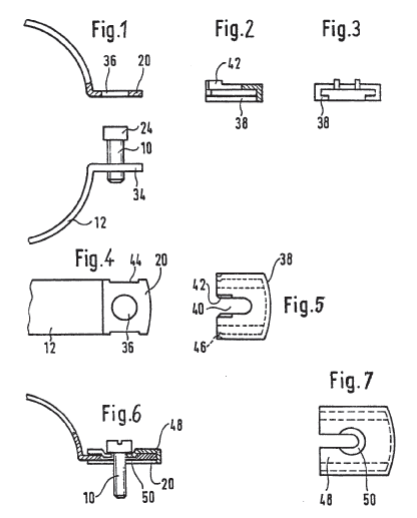

"A pipe clamp comprising an annular strap (12) with at least one opening which can be closed by a clamping screw (10), the tip of which is mounted on one side of the opening by thread engagement and the head (24) of which on the other side of the opening can be passed through and located in a hole (36) in a flange (20) attached to the strap (12), characterised in that the head (24) of the clamping crew (10) can be passed axially, relative to its central longitudinal axis, through the hole (36) in the flange (20) and is retained by a washer (38) which is inserted between the head (24) and the flange (20) before tightening takes place and which is formed with a slot (40) open at one end." (...)

The defendant (...) is a distributor of pipe clamps (...). European patent 0 471 989 was granted therefor in 1993, the patent in dispute being taken into account. The plaintiff sued the defendant for a patent infringement in the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany (...).

The Regional Court (Landgericht) found in favour of the plaintiff. The court of appeal (Berufungsgericht) (...) found in favour of the defendant. In the petition for review (Revision), the plaintiff is seeking restoration of the Regional Court's judgment. The defendant requests that the petition be dismissed.

Extract from the reasons

The petition for review is unsuccessful.

I. 1. The invention concerns a pipe clamp comprising an annular strap with at least one opening which can be closed by a clamping screw (column 1 line 4 ff of the specification of the patent in dispute).

Pipe clamps of this kind were known on the priority date of the patent in dispute. According to the specification of the patent in dispute (column 1, lines 13-33), such a pipe clamp is, for example, described in the German published patent application (Offenlegungsschrift) 3 308 459. (...) The specification of the patent in dispute also considers the pipe clamp known from the German published patent application 3 346 423 (column 1, lines 34-54) (...).

2. On this basis, the problem to be solved by the patent is described as providing a pipe clamp of the known kind "which is easy to operate and can be easily closed, even with a very short clamping screw ". (...)

Specifically, the solution to the problem is made up of a combination of the following features:

1. The pipe clamp consists of

(a) an annular strap (12)

(b) with at least one opening,

(c) which can be closed by a clamping screw (10).

2. The tip of the clamping screw (10) is mounted by thread engagement on one side of the opening.

3. The head (24) of the clamping screw (10) can be

(a) passed through a hole (36) in a flange (20) attached to the strap (12) on the other side of the opening, and more particularly

(aa) relative to its central longitudinal axis,

(b) and is retained there by a washer (38)

(aa) which is formed with a slot (40) open at one end and

(bb) which is inserted between the head (24) and the flange (20) before tightening takes place. (...)

II. The Senate has consistently held that the interpretation given to a patent in dispute by the judge who decides on the facts can subsequently be reconsidered in full by the court of review (Revisionsgericht). The latter is not bound by the interpretation of the court of appeal; rather it may interpret the patent in dispute itself (inter alia, judgment of 22 March 1983 - X ZR 9/82, GRUR 1983, 497, 498 - "Settling device" (Absetzvorrichtung); judgment of 26 September 1996 - X ZR 72/94, GRUR 1997, 116, 117 - "Catalogue holder" (Prospekthalter) and further authorities). Its interpretation will nevertheless be based on the facts established by the appeal court judge; these (…) are binding on the court of review, unless admissible and well-founded grounds for calling them into question have been raised. Such a question of fact arises if, when the subject-matter of the invention as disclosed in the patent specification is being ascertained, it is established how an average person skilled in the art would understand the terms used in the claims, taking into account the description and drawings, and precisely which ideas he would associate with the described concept of the invention (inter alia judgment of 20 December 1979 - X ZR 85/78, GRUR 1980, 280, 281 - "Roller shutter rail" (Rolladenleiste); judgment of 22 September 1983 - X ZR 9/82, GRUR 1983, 497, 1987 - "Settling device" (Absetzvorrichtung); judgment of 26 September 1996 X ZR 72/94, GRUR 1997, 116 "Catalogue holder" (Prospekthalter); cf. also judgment of 5 June 1997 - X ZR 73/95, NJW 197, 3377 - "Steeping device" (Weichvorrichtung) II1).

III. 1. The court of appeal made the following main observations on the only disputed feature 3 (b) (bb) in claim 1 of the patent in dispute: What a person skilled in the art would understand is determined by what is sought to be achieved with the feature "inserted washer". A person skilled in the art would recognise that such pipe clamps could only be fitted with screws of minimum length, and that a minimum amount of turning would only be required to tighten the screws, if, after the screw head has been passed through the hole in the flange, the washer is put into the clamping position on a path between the levels created by the surface of the flange and the screw head's tightening surface. (…)

2. The petition for review criticises the court of appeal for misinterpreting feature 3 (b) (bb) as meaning that the washer is put into the clamping position linearly (translatorily) and not on an orbital path. (...) The court of appeal had thus limited the main claim of the patent in dispute to less than its wording. This interpretation had ignored the principles on the interpretation of patent specifications established in precedents, and disregarded essential submissions made by the plaintiff. (…)

3. The petition for review is unsuccessful in this criticism.

(a) The court of appeal correctly starts from the principles for interpreting a European patent developed by the Senate in its consistent case law. Pursuant to Article 69(1) EPC, the extent of protection conferred by a patent is determined by the terms of the claims, the description and drawings being used to interpret those claims. "Terms" does not mean the literal wording, but rather the essential meaning. What is decisive (...) is the disclosure in the published patent specification to the extent that this is reflected in the claims. This is made clear in the Protocol on the Interpretation of Article 69(1) (...), according to which the interpretation serves not only to resolve any ambiguities in the claims but also to clarify the technical terms used therein, as well as to clarify the significance and scope of the invention (consistent case law of the Senate in BGHZ 105, 1 - Ion analysis (Ionenanlayse)2; BGHZ 133, 1 - "Apparatus for washing vehicles" (Autowaschvorrichtung)3; re section 14 Patent Act (PatG) cf. also: BGH Z 98, 12 - "Moulded curbstone" (Formstein)4). What is decisive for the assessment is the vantage point of a person skilled in the art in the respective specialised field. Terms in the claims and description must therefore be construed as they would be by the average person skilled in the art according to the overall content of the patent specification, taking into account the invention's problem and solution (judgment of 31 January 1984 - X ZR 7/82, GRUR 1984, 425, 426 - "Beer fining agent" (Bierklärmittel); judgment of 26 September 1996 - X ZR 72/94, GRUR 116, 117 f - "Catalogue holder" (Prospekthalter); judgment of 29 April 1997 X ZR 101/93, GRUR 1998, 133, 134 - "Plastics processing plant" (Kunststoffaufbereitung).

From the vantage point of a reader skilled in the art, according to the literal wording of feature 3 (b) bb) of claim 1 of the patent in dispute, protection is being sought only for a washer introduced between the screw head and the flange prior to tightening. The literal wording does not indicate how the washer is placed into the clamping position. In order to be able to understand the essential meaning and significance of this feature, the person skilled in the art would try to determine what the invention is seeking to achieve with the disputed feature. The understanding of a person skilled in the art would therefore fundamentally depend on the purpose of the individual feature as expressed in the patent specification (Benkard/Ullmann, Patentgesetz Gebrauchsmustergesetz, 9th edition, section 13 Patent Act (PatG) margin No. 72). In so doing, the person skilled in the art would not only consider the literal wording of all the claims, but would also draw upon the overall content of the specification of the patent in dispute. If the state of the art tells him that an interpretation in one direction or another is out of the question, perhaps because the device concerned does not appear to be enabling, he will reject this potential interpretation, even if it is a possible one according to the literal wording. In such a situation, the teaching characterised by the patent is limited to the remaining embodiment which the state of the art known to the average person skilled in the art admits as being enabling and which would thus be the only one he would consider. The terms of a patent specification can therefore restrict a patent's disclosure if the person skilled in the art would infer a narrower teaching from the patent specification as a whole than that which the literal wording of a feature appears to convey (cf. Benkard/Ullmann, loc. cit., section 14 Patent Act (PatG) margin No. 67).

(b) The court of appeal (…) established the essential meaning of claim 1 of the patent in dispute accordingly. In so doing, it determined how a person skilled in the art (...) would understand the term "inserted washer" in claim 1 of the patent in dispute (…). According to the (...) findings of the court of appeal, the person skilled in the art would recognise, on the basis of the information conveyed to him by the specification of the patent in dispute concerning the state of the art and the technical problem to be solved by the invention, that the long screws and screw distances used in the state of the art are consequences of the unfavourable movement between the head of the clamping screw and the clamping flange and not the consequences of the "state of insertion". Furthermore he would recognise that, according to one of the solutions in the state of the art, long screws are required because the head of the screw is moved into the clamping position on an orbital path with the axis of its rotation near the flange, whereas according to the other solution in the state of the art, long screws are required because the head of the screw and the flange surface are brought together into the clamping position on an almost cycloid or involute-shaped path. This knowledge would prevent the person skilled in the art from understanding the teaching of feature 3 (b) (bb) in the sense of the petition, ie that the only relevant factor is the "state of insertion". Rather he would construe this teaching to refer to the path on which, or the type of movement with which, the washer is brought into the clamping position. (…)

This (...) essential meaning, as established by the court of appeal and accepted for the purposes of the review procedure, does not constitute a limitation to less than the literal wording, but rather an interpretation in accordance with that literal wording, as a person skilled in the art would be bound to construe it on the basis of the overall content of the specification of the patent in dispute.

(c) The petition for review cannot counterclaim that, according to the literal wording of feature 3 (b) (bb), (...) the key factor is not the movement of inserting the washer, but rather the condition achieved by the "insertion" (…). It can be left open whether in general technical use of language the word "inserted" is understood in this way. Interpreting a patent does not entail adhering strictly to the wording, but rather considering the overall technical context conveyed by the content to the average person skilled in the art. The claim is to be interpreted not literally in a philological manner, but rather according to its technical sense, that is to say the idea behind the invention must be established, having regard to the problem and solution as they are derived from the patent. The Senate has therefore rejected the purely linguistic interpretation of a term used in the patent specification and has instead considered the technical sense of the words and terms used therein (judgment of 30 June 1964 - X ZR 109/63, GRUR 1964, 612, 615 - "Beer racking" (Bierabfüllung); judgment of 12 November 1974 - X ZR 76/68, GRUR 1975, 422, 424 - "Roughing-down roll II" (Streckwalze II), cf. also for the opposition proceedings the Senate's order of 17 January 1995 - X ZB 15/93, GRUR 195, 330, 332 - "Electric jumper cable" (Elektrische Steckverbindung)). This also applies to the interpretation of a European patent. What is decisive is therefore not the linguistic or logical conflation of terms, but rather how those terms would be understood by a person skilled in the art in practice (...). This opinion is, as far as it is possible to judge, also shared in other European countries (cf. EPO GRUR Int. 1994, 59, 60, 61 - "Washing composition/UNILEVER" (Waschmittel/UNILEVER)5, and other authorities; House of Lords GRUR Int. 1982, 136 - "Steel lintels" (Stahlträger II); Court of Appeal R.P.C. 1997, 737, 752).

(...) Although everyday use of language and general technical use of language can give an indication of what the understanding of a person skilled in the art would be (…), it must nevertheless always be taken into account that the terms used in patent specifications constitute their own kind of glossary, that the terms may be used differently from everyday use of language and that, ultimately, only the connotation derived from the patent specification is decisive. For that reason, the clearer the wording of the feature and its meaning appear to be from the content of the patent specification, the less scope there will be for recourse to everyday use of language (…).

(e) The petition for review cannot succeed with its objection that, when interpreting the European patent in dispute, the court of appeal should have taken into account the English and French versions. Pursuant to Article 70(1) EPC, the text of a European patent in the language of the proceedings is the authentic text in every contracting state (...). The wording of the claims in the other official languages of the European Patent Office, on the other hand, carries no weight. It merely allows conclusions to be drawn on how the translator understood the text in the language of the proceedings. (…)

IV. The court of appeal found that the pipe clamp at issue did not infringe the patent in dispute because neither pursuant to the wording nor by any equivalent means under patent law did the pipe clamp make any use of the teaching of claim 1.

1. (...)

2. The court of appeal held that there was no literal implementation of the disputed feature 3 (b) (bb). In this connection it observed the following: In the case of the contested embodiment, the impactor plate (washer) is not "introduced" prior to tightening in a straight line between the head and the flange within the meaning of the disputed feature, but rather it is brought into the clamping position on an orbital path whose centre of rotation is near a pipe clamp flange. The contested embodiment thus refrains from using the teaching of feature 3 (b) (bb) and, as regards the way in which the head of the screw and the clamping surface of a pipe clamp flange move, uses the circular motion known from the state of the art, which is not what is meant by the "insertion" of the washer between the head and the flange as addressed in feature 3 (b) (bb).

The objections to this raised in the petition for review do not succeed.

(...) What is decisive is that, in contrast to the teaching of the patent in dispute, the impactor plate in the case of the contested device is brought into the clamping position on an orbital path and, as a result of this type of motion, dispenses with precisely the advantages intended through the insertion of the washer within the meaning of feature 3 (b) (bb).

3. Nor, In the opinion of the court of appeal, is the contested pipe clamp equivalent to the patented solution under patent law, because the means claimed by the plaintiff do not correspond in their technical function to the patented means and do not have a substantially equivalent effect. (…)

The petition for review asserts that the court of appeal should also have examined whether the infringing embodiment of the protected device is equivalent under patent law in the sense of being an "inferior embodiment", it being sufficient according to case law for the contested embodiment to achieve the advantages of the invention to a practically significant extent. This, it is claimed, is the case here if, contrary to the opinion of the court of appeal, the inventive achievement of the patent in dispute is assumed not to be limited to the objective of providing a pipe clamp which can be used with the shortest possible clamping screws.

Here too the petition for review fails. (…) As has already been explained above and was correctly established in the impugned judgment, the shortening of the clamping screws and clamping distances is clearly the focus of the teaching of the patent in dispute. It is not merely one of several roughly equivalent subsidiary aspects, as the petition claims. The teaching of the patent in dispute is also not limited to a "certain shortening" of a completely undefined magnitude; rather the emphasis is on enabling the use of "very short" screws which can be tightened "with just a few turns" (column 1, line 54; column 2, lines 7-9). It is precisely this which is not achieved by the contested embodiment (…). There can therefore be no question of the problem underlying the protected invention - how to provide very short clamping screws and very short clamping distances - being solved by the contested embodiment to an extent which still has practical significance. Thus a crucial precondition for a patent infringement by equivalent means has not been met. According to the principles which the Senate has developed from the old law, there is equivalence for the purposes of patent law only if the problem and technical achievement of the conflicting embodiments are the same, but the means used to solve the problem and thus to achieve the same success are different. What is required, therefore, is that the alternative means used in the contested embodiment, instead of the means expressly recommended in the patent, serves to solve the specific problem posed in the patent and - at least substantially - achieves the success sought by the patent (Federal Court of Justice (BGH), judgment of 14 July 1966 - Ib ZR 79/64, GRUR 1967, 84, 85 - "Christmas tree hanging decorations II" (Christbaumbehang II); judgment of the Senate of 29 April 1997 - X ZR 101/93, GRUR 1998, 133, 135 - "Plastics processing plant" (Kunststoffaufbereitung); cf. also Austrian Supreme Court (ÖOGH), judgment of 3 April 1984, GRUR Int. 1985, 766, 767; Benkard/Ullmann, loc. cit. , section 14 margin No. 130, 149). These principles also apply for assessing the extent of protection conferred by a European patent. They correspond to the principle, developed in English case law in the so-called "Catnic" questions and also applied to the extent of protection conferred by European patents, whereby deviations fall outside the extent of protection conferred by a patent if they have significant effects on the way in which an invention works (cf. Court of Appeal of 16 June 1995 in the case K.v.R., GRUR Int. 1997, 374 - "Cigarette Papers" (Zigarettenblättchen). The extent of protection conferred by a European patent cannot therefore be extended to embodiments using alternative means which, either completely or to an extent which is no longer of practical significance, dispense with the success sought by the patent. (...)

DE 2/01

* Official headnote and extract from the reasons for the decision which are published in full in Mitteilungen der deutschen Patentanwälte (Mitt.) 1999, 304.